A personal essay about algorithms, aesthetics, and the small acts of borderless connection that survive politics, postage, and translation.

My Instagram algorithm has become a model United Nations where all the delegates wear linen co-ord sets. Every third reel shows a woman twirling in natural light, somewhere between Kyiv and Karachi. The captions resist translation, even Google gives up, Meta AI hallucinates something like “dreams woven by dawn.” I double-tap anyway.

This is how I learned the world is smaller than we think and farther than we’ll ever reach.

The Language of Longing

Each purchase teaches me translation is impossible. Not just the captions, though those remain sealed in Cyrillic, Arabic, Hangul, but everything else too. How do you translate the weight of 30 euros (written 30,00, even punctuation has borders) into rupees? How do you translate handmade when the hands belong to a Syrian refugee in Vienna?

A Polish lace handkerchief takes three months to travel from Kraków to Bangalore. I track it through five countries, watch it disappear in Doha for reasons unknown, whisper “Ab Dilli door nahin” and sigh in relief when it finally hits Gurgaon, though I live two thousand kilometres south. The Sufi warning inverted into a courier prayer.

The deeper I scroll, the stranger the map becomes. Ukrainian embroidery appears between reels of coffee shops and cats. The seller doesn’t mention the war, but her shipping times tell me everything. In Lviv, someone embroiders while air-raid sirens wail. In Karachi, someone block-prints fabric during load-shedding. In Istanbul, someone throws ceramics while protests echo outside. In Kashmir, a weaver’s family walked from Srinagar to Muzaffarabad in 1947; now the pashmina goats cross the Line of Control but the artisan cannot.

The algorithm doesn’t show this part. It only shows the golden hour, the perfect flat lay, beauty scrubbed clean of its conditions.

Every object looks designed to heal trauma.. and maybe it was.

Borders in the Algorithm

A kurta appears, block-printed, shot in that particular north-Indian afternoon light that makes everything look like memory. The vocabulary feels familiar, prices in rupees. You message: “How much for the embroidered one?”

They reply: “12,000.”

Then instinct kicks in. You scroll back up to check the bio.

The address says Lahore.

Your stomach drops. Not gradually, all at once, like missing a step in the dark. You reread your message, scanning for anything that could be misunderstood, misconstrued, misused. It’s just a question about a kurta. Just fabric and thread. But you’re already calculating: Does the message show as “seen”? Can you unsend it before they notice? What if someone is watching? Not them, someone else. Someone on either side of the border, keeping track of the wrong kind of curiosity.

You delete the message like someone erasing footprints at a border.

My grandmother could have been born in Sialkot, fifty kilometres from Lahore. She might have bought fabric from their grandmother’s shop, might have walked those same bazaar lanes before the lines were drawn. Now I delete a message about a kurta like I’m committing treason, because even digital curiosity feels dangerous.

Seventy years. Seventy kilometres. The fabric is identical, the aesthetics indistinguishable, the algorithms the same. We’re speaking in the same mix of English-Urdu-Hindi, converted to the same Roman script, using the same emoji.

The AI doesn’t care about Partition. It only knows that people who like Lucknowi chikankari also like Karachi’s shadow work. The algorithm is writing a peace treaty our governments would never sign.

The Fellowship of the Internationally Fooled

The algorithm doesn’t only curate beauty. Sometimes what crosses borders most easily is deception.

Every Indian with a phone knows the domestic-scam routine: “Sir, only today 70 percent off on pure silk saree.” You can threaten them with cyber-crime complaints, wave around your uncle who knows the DCP (Deputy Commissioner of Police), or at minimum, creatively insult their lineage in Hindi. There’s comfort in that familiar betrayal.

But globalization has democratized deception too. Now the scammer is in Azerbaijan, selling rugs that exist only as stolen Pinterest images. The invoice arrives in Cyrillic; the Instagram account vanishes. You’re left explaining to your bank why you sent money to OÜ Craftology, registered in Estonia, operating from Baku.

You’ve joined a new kind of global citizenship: the fellowship of the internationally fooled.

This, too, is a kind of translation: learning that “handcrafted in small atelier” means factory in Guangzhou; that “ships in 2-3 days” means weeks of watching your package live a life more adventurous than your own.

The Myth of Origin

Sometimes the deception is more subtle, not fraud exactly, but mythology.

Yesterday, a wallet appeared claiming to be “handcrafted from Napa leather in a small atelier in Napa.” A place so committed to its brand it became the product.

We still believe in the magic of place: Italian leather, Japanese minimalism, Turkish ceramics, Kashmiri wool. As if buying something also buys you into its geography, its history, a story older and purer than yourself. The marketing works because we want it to work. We want the linen dress to carry the weight of Mediterranean sun, the ceramic bowl to hold centuries of Anatolian craft tradition, the embroidered blouse to connect us to grandmothers in Lviv we’ll never meet.

But what am I actually buying when I double-tap on a “vintage Japanese kimono” sold by an account in Los Angeles? Am I appreciating craft or appropriating costume? The algorithm doesn’t ask. It only knows I also liked that Korean hanbok-inspired jacket, that Indian block-print kurta, that Moroccan babouche slippers. It thinks I’m building a wardrobe. I think I’m building a self, one educated enough to recognize beauty across cultures, worldly enough to wear it without flinching.

The line between appreciation and fetishization is supposed to be intention, context, respect. But Instagram collapses all of that into: do you have the right credit card? Can you pull off the aesthetic?

I buy a suzani throw from Uzbekistan. Or I buy something made in Guangzhou that claims to be suzani from Uzbekistan. Or I buy something actually from Uzbekistan but made for Western Instagram aesthetics, not local use, a craft tradition performing itself for an audience that will never understand its original context. Which of these constitutes respect? Which is theft?

The digital transaction erases the possibility of knowing. There are no hands to shake, no workshop to visit, no way to verify that the “family recipe” isn’t just a good caption. Everything is mediated through the same grid of perfect squares, the same language of golden hour and “slow living” and “ethically sourced.” The aesthetic is the only truth we have access to.

And maybe that’s why place matters so much in the marketing, because in a transaction made of zeros and ones, “Made in Italy” or “Handwoven in Oaxaca” is the only anchor to something real, something you can almost believe existed before the algorithm found it and recommended it and made it shoppable with one tap.

PayPal becomes a map of American foreign policy: Iran blocked, Russia restricted, Palestine complicated. Some places you can want from. Others you cannot. The payment processor decides which borders matter.

When parcels finally arrive, travel-worn, customs-cleared, covered in stickers in scripts I can’t read, I hold them like letters from a world that doesn’t quite exist. Not the fantasy the algorithm sold me, but something more honest: proof that despite everything, someone somewhere made something beautiful and found a way to send it across all the borders between us.

And maybe that’s enough. Not certainty about origin or purity of intention, but this: someone made it, I wanted it, it arrived. The rest is mythology we drape over commerce to make it feel like connection.

The Peace Treaty

“Hanooz Dilli dur ast,” the Sufis warned, Delhi is still far. They meant power, but I whisper it to tracking pages and customs forms. My Ukrainian embroidery waits next to someone’s Korean skincare, someone’s Brazilian coffee, someone’s Pakistani textiles (mislabelled as Indian, for obvious reasons).

We’re all awaiting clearance, really.

Sometimes I think my algorithm knows something our governments don’t, or won’t admit. That a girl in Bangalore and a girl in Lahore will always want the same kurta. That beauty refuses borders even when bodies can’t cross them.

My For You Page is the peace treaty, not between nations but between people who double-tap despite not understanding the caption, who calculate shipping costs like computing the price of longing, who delete messages but save the seller’s handle anyway, just in case history changes its mind.

When the Polish handkerchief finally clears customs: fifteen thousand rupees for a cotton square, three months in transit, I unfold it like something sacred. White cotton, edges scalloped with lace so delicate it seems to dissolve at touch. I think of the hands that made it, the five countries it crossed, the customs officers who examined it and decided it was harmless enough to pass through.

The internet promised to eliminate distance. Instead, it made distance visible, measurable, painful, and somehow crossable, if you’re willing to pay for shipping.

I use the handkerchief to clean my phone screen now, wiping away the fingerprints from all that scrolling, all that double-tapping across borders I’ll never cross.

Maybe that’s all peace ever was: not the absence of borders but these small insistences on beauty despite them.

The package that arrives against all odds.

The translation that fails but tries anyway.

The kurta from Lahore saved in a folder marked Someday.

The double-tap that says: I see you, even if I’ll never meet you. Even if I can’t read your words. Even if history says I shouldn’t.

Postscript

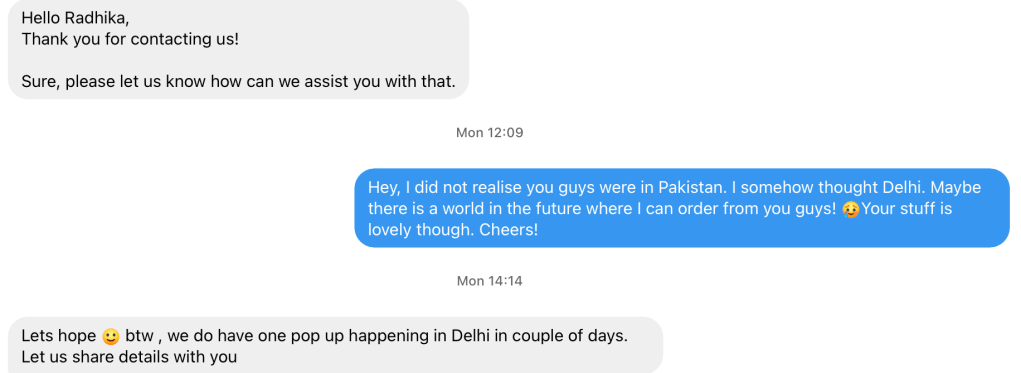

A few days after finishing this essay, my For You page staged its own experiment in soft diplomacy. I saw a stunning white kurta, delicate embroidery, elegant styling, the sort of thing that makes you pause mid-scroll. The account said Galleria, and without thinking, I assumed DLF Galleria, Delhi. I sent a message asking about the price.

A few minutes later, while browsing the rest of their feed, I noticed the tag: #Pakistan. I searched the address and realized the store was in Lahore.

The same stomach-drop. The same paranoid scan of what I’d written. I tried to delete the message. It had already gone through.

Then my phone buzzed, the vibration sharp against my palm. A notification from Instagram.

I opened it like someone defusing something, careful and slow.

The reply was friendly, professional. They answered my question. I stared at it, then wrote back: an apology, an explanation, an expression of regret wrapped in a compliment:

“Hey, I did not realise you guys were in Pakistan. I somehow thought Delhi. Maybe there is a world in the future where I can order from you guys! 😭 Your stuff is lovely though. Cheers!”

The crying emoji doing the work I couldn’t figure out how to do with words. Grief for a border I didn’t draw. Hope for a future I don’t control. An apology for wanting something I’m not supposed to want.

Their response came quickly:

“Let’s hope 🙂 Btw, we do have one pop-up happening in Delhi in a couple of days. Let us share details with you.”

Btw.

By the way.

As if it were the most natural thing in the world. As if I hadn’t just apologized for geography. As if Lahore to Delhi weren’t a border but just a distance: four hundred kilometres, a five-hour drive, closer than I am in Bangalore, two thousand kilometres south.

I sat there holding my phone, reading btw over and over, the casual mundanity of it, the erasure of my entire emotional crisis in two words, a semicolon, and a smiley face.

I’d been writing an essay about borders and longing and impossible crossings, mapping my grief onto their business model. They were just… running a business. Doing a pop-up in a nearby city. The way anyone would.

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe the peace treaty isn’t dramatic.

Maybe it’s just btw.

Subscribe if you’d like to read more of my attempts to make sense of things through words.

Leave a comment